Tag: facebook

LinkedIn and Facebook Are Different (For Me)

by chris on Aug.25, 2012, under general

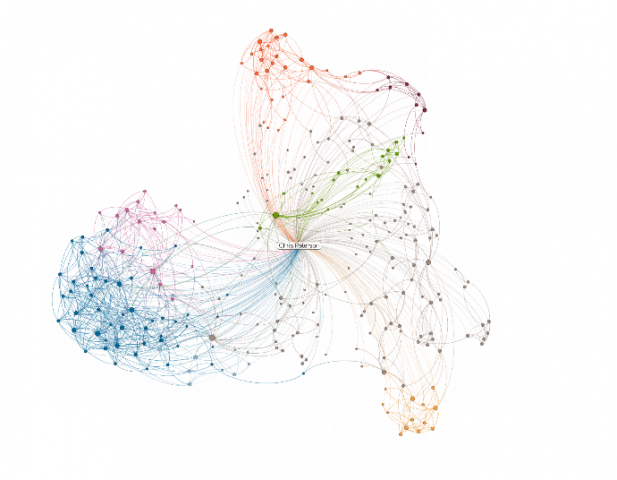

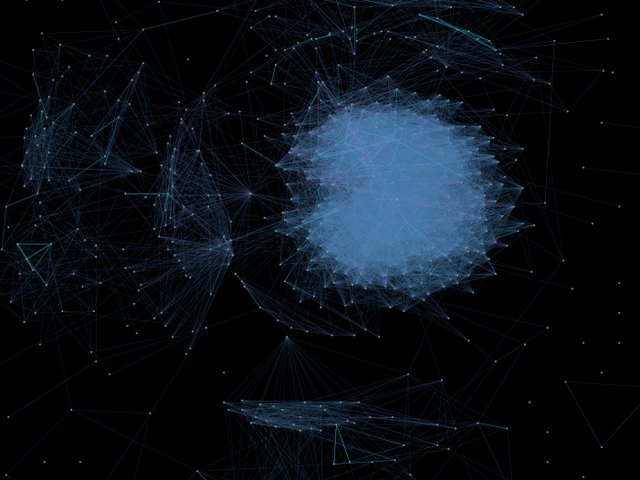

@mstem clued me in to LinkedIn’s new “InMaps” feature, which allows you to visualize your LinkedIn network:

Most striking to me was how my LinkedIn network differs topographically from my Facebook network, generated a year or so ago by the Nexus application:

For most people, social network sites are constituted and animated by the social networks which preexist them in the physical world. The sites themselves merely shape the contours of these networks as they are represented in those spaces. Fascinating for me to see visually what I already new intuitively: that despite both being “social network sites”, LinkedIn and Facebook are very socially for me.

Facebook, Network Effects, and the Birth of Giants

by chris on Jun.04, 2012, under general

Benjamin Mako Hill, an excellent activist and academic associated with the Center for Civic Media and Berkman Center (among others), has a widely-circulated blog post up entitled Why Facebook’s Network Effects are Overrated. This is something I wrote about in Losing Face.

Ben makes a lot of really good points, but there are a few with which I disagree, and I wanted to comment on them further here. He writes:

And the relationships between services aren’t always peaceful coexistence. Remember Friendster? Remember Orkut? Remember Tribe? Remember MySpace? MySpace, and all the others, are great examples of how social networks die. They very slowly fade away. MySpace users signed up for Facebook accounts and used both. They almost never just switched. Over time, as one platform became more attractive than the other, for many complicated reasons, attention and activity shifted. People logged in on MySpace less and Facebook more and, eventually, realized they were effectively no longer MySpace users. Anyone that has been on the Internet long enough to watch a few of these shifts from one platform to another knows that they’re not abrupt — even if they can be set in motion by a particular event or action. Users of social networking sites simply don’t have to choose in the way that a person choosing to boot Windows and GNU/Linux does.

First, Facebook is bigger than these other examples. A lot bigger. So much bigger, in fact, that I would argue the difference is of character, not of degree. Metcalfe’s Law tells us that the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system. If this is an accurate way to think about social networks – and I believe it is – then the fact that Facebook now contains almost a seventh of the world’s population is very meaningful. Remember: Ma Bell never died. She had to be killed. And her dismembered bits and pieces are slowly oozing back together.

I don’t think the appropriate comparison for Facebook is MySpace, or Friendster, or Tribe anymore. Those sites remind me, in hindsight, more like Path or Instagram or Pinterest: much smaller, segmented, affinity communities for particular populations. Facebook has become something almost more like electrical current or railway gauges, or even the TCP/IP stack: yeah, there may be global variations, but generally speaking everyone is using the same thing.

Ben was talking about network effects; I’d like to add in the concept of a natural monopoly. It seems to me that it makes sense for there to be one big social network site for everyone. It doesn’t need to be the only one (and Ben makes this point about Diaspora having its own valuable niche). But just in the same way that we’ve realized it doesn’t make sense to have multiple Internets (goodbye CompuServe, goodbye AOL), I’m not sure it makes sense to have multiple social network sites of global aspiration. Facebook is there already. And if Google can’t beat them – with more users worldwide than Facebook has through search, GMail, etc – then no one can in the foreseeable future.

Second, I don’t think the switching costs are lower for social network sites. The Data Liberation Front and Facebook’s archiving system are nice. But they’re also trivial. They’re trivial because the point of privately enclosed social intermediaries is not the things but the people enclosed within them.

Network effects + Metcalfe’s Law means the social network site which contains the largest subset of my set of friends is the most socially useful site to me. There may be design or affinity differences which add a weight to the equation but the general arithmetic holds true. I might have stopped using Facebook a long, long time ago, except that even if I wanted to I can’t; it’s where all of my friends are, where they plan events, where they post links that I find useful / informative / entertaining, and until they are elsewhere I must remain.

That’s a much harder decision to make than what OS to boot into. I can boot my Macbook into OSX / Windows / Ubuntu. For that matter, I can emulate any of them in VMWare. And, because of hard-fought interop battles (and the economics of software publishing houses) I can increasingly rely on some cross-platform compatibility in key software tools. Every day there is less vendor lock-in in the software space that actually limits me. Tableau is Windows only? Fine. I’ll install XP on VMWare and run it under Unity View. To me, the user, it’s transparent. I’m not trying to trivialize interop / OS wars / lock-in here. I just think that, for me, the decision to drop Facebook is about a billion times more difficult than what OS I boot into.

The real thing that is interesting to me, though, is something Ben mentions only in passing, presumably because it is such a complex and difficult question to grapple with:

Over time, as one platform became more attractive than the other, for many complicated reasons, attention and activity shifted.

What exactly did happen here? How the hell did Facebook get so big so fast? How did it penetrate so many markets so completely? And could anyone else do what Facebook did (which it would need to do in order to replace it)?

I don’t know all the answers to all these questions. But I think I’ve got a dim sense of one.

In June 2005, when I was graduating from high school, I remember standing in the high school cafeteria with my friend Erica Getto. We were practicing the graduation walk and chatting idly about life in college. Erica asked me if I had heard of TheFacebook. She had, from her elder brother, and she said that “all college kids are on it” and it was how they kept in touch.

When future historians go back and try to figure out what the key was to Facebook’s success I’d be willing to bet money that it was in their (completely accidental) market positioning. They went very, very deep into the college demographic, which is different from going deep into the hipster demographic or goth demographic or punk demographic because while college students are certainly demographically distinct from their age cohort a lot of different people go to college at one point in their lives. It’s as if rather than Facebook trying to capture one branch of a social tree, they instead caught one four-year long segment of the trunk. The thing is, as time goes on that segment graduates, and then goes out into the world, but still has a Facebook account with all of these ties, and a new group comes in.

In other words the thing that made Facebook a success (I think) is that it deeply penetrated a broad set of people in a narrow set of time / life experience. This meant that people who graduated could still use it, and people who were entering college would get indoctrinated in, and it just grew from them.

Incidentally, I think the same thing is about to happen to Apple. At MIT and at every other college where I have spent time Macs are used at a rate disproportionate to the adult professional population. Most of industry, enterprise, government, etc is still old PC boxes. But Apple has had such deep penetration into a generation of college students that I have to think they will demand (and eventually receive) Macs in the workplace going forward. Anecdotally this has already begun to happen.

Again, this isn’t the only explanation. It’s one explanation in a complex ecology of explanations. But I think there is something to this idea of deeply penetrating a broad-base, time-slice cohort, and then hoping that it grows and networks out as it moves in time. The takeaway is: build a tool that’s useful for a slice, and they, like Rick Astley, will never want to give it up.

Facebook’s “Groups for Schools”: A Harmless Example of a Scary Trend

by chris on Apr.13, 2012, under general

Today brings a guest post from MIT senior (and good friend) Paul Kominers. Full post after the jump.

Facebook Immune System

by chris on Oct.28, 2011, under general

…is the name of the system which protects Facebook from things that look like spam.

And it checks 25 billion actions every day autonomously.

FIS very likely makes Facebook a much better, safer place in most of what it does. But when you’re talking about that scale, you can’t help but think about the problems automated deletion pose for legitimate speech.

Facebook, J30Strike, and the Discontents of Algorithmic Dispute Resolution

by chris on Oct.15, 2011, under general

The advent of the Internet brought with it the promise of digitally-mediated dispute resolution. However, the Internet has done more than simply move what might traditionally be called alternative dispute resolution into an online space. It also revealed a void which an entire new class of disputes, and dispute resolution strategies, came to fill. These disputes were the sorts of disputes that were too small or numerous for the old systems to handle. And so they had burbled about quietly in the darkness – bargaining deep in the shadow of the law and of traditional ADR – until the emerging net of digitally designed dispute resolution captured, organized, and systematized the process of resolving them.

In most respects these systems have provided tremendous utility. I can buy things confidently on eBay with my Paypal account, knowing that should I be stiffed some software will sort it out (partially thanks to NCTDR, which helped eBay develop their system). Such systems can scale in a way that individually-mediated dispute resolution never could (with all due apologies to the job prospects of budding online ombudsmen) and, because of this, actually help more people than could be possible without them.

We might usefully distinguish between two types of digital dispute resolution:

- Online Dispute Resolution: individually-mediated dispute resolution which occurs in a digital environment

- Algorithmic Dispute Resolution: dispute resolution consisting primarily of processes which determine decisions based on their preexisting rules, structures, and design

As I said before, algorithmic dispute resolution has provided tremendous utility to countless people. But I fear that, for other digital disputes of a different character, such processes pose tremendous dangers. Specifically, I am concerned about the implications of algorithmic dispute resolution for disputes arising over the content of speech which occurs in online spaces.

In the 1990s, when the Communications Decency Act was litigated, the Court described the Internet as a civic common for the modern age (“any person with a phone line can become a town crier with a voice that resonates farther than it could from any soapbox”). Today’s Internet, however, looks and acts much more like a mall, where individuals wander blithely between retail outlets that cater to their wants and needs. Even the social network spaces of today function more like, say, a bar or restaurant, a place to sit and socialize, than they do a common. And while analysts may disagree about the degree to which the Arab Spring was faciliated by online communication; it is uncontested that whatever communication occurred did so primarily within privately enclosed networked publics like Twitter and Facebook as opposed to simply across public utilities and protocols like SMTP and BBSes.

The problem, from a civic perspective, of speech occurring in privately administered spaces is that it is not beholden to public priorities. Unlike the town common, where protestors assemble consecrated by the Constitution, private spaces operate under their own private conduct codes and security services. In this enclosed, electronic world, disputes about speech need not conform to Constitutional principles, but rather to the convenience of the corporate entity which administrates the space. And such convenience, more often than not, does not concord with the interests of civic society.

Earlier this year, in June 2011, British protestors launched the J30Strike movement in protest of austerity measures imposed by the government. The protestors intended to organized a general strike on June 30th (hence, J30Strike). They purchased the domain name J30Strike.org, began blogging, and tries to spread the word online. Inspired, perhaps, by their Arab Spring counterparts, British protestors turned to Facebook, and encouraged members to post the link to their profiles.

What happened next is not entirely clear. What is clear that on and around June 20th, 2011, Facebook began blocking links to J30Strike. Anyone who attempted to post a link to J30Strike received an error message saying that the link “contained blocked content that has previously been flagged for being abusive or spammy.” Facebook also blocked all redirects or short links to J30Strike, and blocked links to sites which linked to J30Strike as well. For a period of time, as far as Facebook and its users were concerned, J30Strike didn’t exist.

Despite countless people formally protesting the blocking through Facebook’s official channels, it wasn’t until a muckraking journalist Nick Baumann from Mother Jones contacted Facebook that the problem was fasttracked and block removed. Facebook told Baumann that the block had been “in error” and that they “apologized for [the] inconvenience.”

Some of the initial commentary around the blocking of J30Strike was conspiratorial. The MJ article noted a cozy relationship between Mark Zuckerberg and David Cameron, and others worried about the relationship between Facebook and one of its biggest investors, the arch-conservative Peter Thiel.

Since Facebook’s blocking process is only slightly more opaque than obsidian, we are left to speculate as to how and why the site was blocked. However, I don’t think one needs to reach such sinister conclusions to be troubled by it.

What I think probably happened is something like this: members of J30Strike posted the original link. Some combination of factors – a high rate of posting by J30Strike adherents, a high rate of flagging by J30Strike opponents, and so forth – caused the link to cross a certain threshold and be automatically removed from Facebook. And it took the hounding efforts of a journalist from a provocative publication to get it reinstated. No tinfoil hats required.

But even this mundane explanation deeply troubles me. Because it doesn’t matter, from a civic perspective, is not who blocked the link and why. What matters is that it was blocked at all.

What we see here is an example of algorithmic censorship. There was a process in place at Facebook to resolve disputes over “spammy” or “abusive” links. That process was probably put into place to help prevent the spread of viruses and malicious websites. And it probably worked pretty well for that.

But the design of the process also blocked the spread of a legitimate website advocating for political change. Whether or not the block was due a shadowy ideological opponent of J30Strike or to the automated design of the spam-protection algorithm is inconsequential. Either way, the effect is the same: for a time, it killed the spread of the J30Strike message, automatically trapping free expression in an infinite loop of suppression.

What we have here is fundamentally a problem of dispute resolution in the realm of speech. In public spaces, we have a robust system of dispute resolution for cases involving political speech, which involves the courts, the ACLU, and lots of cultural capital.

Within Facebook? Not so much. On their servers, the dispute was not a matter of weighty Constitutional concerns, but reduced instead to the following question: “based on the behavior of users – flagging and/or posting the J30Strike site – should this speech, in link form, be allowed to spread throughout the Facebook ecosystem?” An algorithm, rather than an individual, mediated the dispute; based on its design, it blocked the link. And while we might accept an blocking error which blocks a link to, say, a nonmalicious online shoe store, I think we must consider blocks of nonmalicious political speech unacceptable from a civic perspective. We have zealously guarded political speech as the most highly protected class of expression, and treated instances of it differently than “other” speech in recognizance of its civic indispensability. But an algorithm is incapable of doing so.

This is censorship. It may be accidental, unintentional, and automated. We may be unable to find an individual on whom to place the moral blame for a particular outcome of a designed process. But none of that changes the fact that it is censorship, and its effects just as poisonous to civic discourse, no matter what the agency – individual or automaton – animating it.

My fear is that we have entered an inescapable age of algorithmic dispute resolution. That we won’t be able to inhabit (or indeed imagine) digital spaces without algorithms to mediate the conversations occurring within. And that these processes – designed with the best of intentions and capabilities – will inevitably throttle the town crier, like a golem turning dumbly on its master.

This post originally appeared on the site of the National Center for Technology and Dispute Resolution.

The Facebook Disease: Real Identity, Radical Transparency, and Randi Zuckerberg

by chris on Aug.03, 2011, under general

Via Eva Galperin for EFF:

Speaking last week on a panel discussion about social media hosted by Marie Claire magazine, [Facebook Marketing Director Randi] Zuckerberg said,“I think anonymity on the Internet has to go away. People behave a lot better when they have their real names down. … I think people hide behind anonymity and they feel like they can say whatever they want behind closed doors.”

Let me note at the outset that Randi Zuckerberg was not completely wrong. People do tend to behave better when they have their real names – or, more specifically, their “real life” – attached to the things they say or do on the Internet.

That’s because shaming works. I don’t think that’s a controversial statement. And Facebook has gotten a lot of mileage out of shaming. They don’t call it shaming, of course. They have some fancy name for it – RealSocial or something, I forget – but Chris Kelly, the former Facebook Privacy Officer, used to talk about it all the time. Here’s him describing the policy in high-minded terms in The Facebook Effect:

We’ve been able to build what we think is a safer, more trusted version of the Internet by holding people to the consequences of their actions and requiring them to use their real identity.

So, premise: tying people’s online identities to their “real” identities will, through shaming and social norms, make them behave better, or, more precisely, more like they do “in real life.”

I don’t think anyone disputes that.

The problem is in the conclusion: that, because this premise is true, “anonymity on the Internet needs to go away.”

Eva, the author of the EFF post, already hit most of the usual (but worth reiterating!) points why the conclusion is total bullshit: because “activists living under authoritarian regimes, whistleblowers, victims of violence, abuse, and harassment, and anyone with an unpopular or dissenting point of view that can legitimately expect to be imprisoned, beat-up, or harassed for speaking out” benefit from anonymity and pseudonymity (which the Facebook policy also prohibits). It goes without saying that anyone with an elementary education – and I mean literally an elementary education, we’re talking Federalist Papers here – should be able to appreciate the importance of hiding your name in order to speak your mind. And it goes without saying that we should all be glad that Randi Zuckerberg is not part of the IETF.

But I’d like to make one other connection here.

This fetishization of onymity (yes, that is the antonym of anonymity!) is not an isolated blemish on the face of Facebook. It is but one of several symptoms of a deeply rooted disease: Facebook’s love of radical transparency.

Read danah boyd on Facebook and radical transparency before you read any more of me, but the practical upshot is that Zuckerberg – Mark this time – has said repeatedly that, basically, the world would be better off if everybody was open about everything all of the time, and that anything short of that was a “lack of integrity”.

Now, anyone who has read their boyd, Warner, Goffman, Meyrowitz, or even Jarvis (or even me) will realize how almost unbelievably dumb – or shall we say “conceptually incoherent” – this statement is. No one actually lives like that. That’s not how social norms work. That’s not how privacy works. And Zuckerberg, of course, does not himself live a radically transparent lifestyle either, or else you’d be able to see a whole lot more on his Facebook profile.

But I want to underline the fact that the Zuckerbergs are not merely wrong in their pathological obsession with radical transparency and “real identity.” They are wrong in a way which actively hurts people. Again, not to crib too heavily from boyd here, but there are reasons why things like pseudonyms and privacy settings matter. They don’t really matter to people like the Zuckerbergs – people who have money, education, protection, and prestige. They matter to the subaltern.

Think about it for literally one second. What it means to be “radically transparent”, and how it affects one’s lived experience, depends entirely on one’s position in society. More concretely: being “radically transparent” about, say, sexuality, means very different things to a straight male student and a closeted gay student in a homophobic, conservative high school context. That’s a very simplistic example, but a very powerful one. And dismissing those concerns is more than merely incorrect. It harms those who are the most vulnerable.

If you ever wondered why Facebook is one of the most hated companies in America, you can stop now. The answer is evident. It’s captained by fools – or brigands. And when (not if) the karmic collapse comes – when something finally arrives to take Facebook’s place – there will be no love lost for it.

Nor will it deserve any.

e: a Facebook employee who I know and trust sent me some thoughtful comments via email. Without quoting them in full, they boil down to: despite whatever crazy things the Zuckerbergs might say to reporters, we engineers actually spend a lot of time trying to work within the existing privacy infrastructure, and to make it better as we can.

And I believe that’s true. Facebook has actually has pretty powerful privacy settings for a long time, even if they are hidden and poorly publicized. But I don’t think (most) of the rank and file engineers at Facebook are into radical transparency. I think they are basically smart people working on a really tough and complex piece of software, and they’re trying to keep it working and keep making it better, and don’t have enough time to make grand announcements about anonymity or really set policy going forward.

I just think the fish is rotting from the head.

Nobody Knows What Google+ Is Yet. And That’s Awesome.

by chris on Jul.28, 2011, under general

This article about the implications of Google+ came across my desk today. It’s a quick post discussing the potential implications of Google+ for higher ed recruitment – whether or not you could (or should) Hangout with prospective students, etc.

It’s a good article, but it’s also premature.

The thing about Google+ is it isn’t a thing yet. By that intentionally inarticulate statement I mean we don’t yet know what the norms and expectations of Google+ are.

Norms and expectations of sites are always changing. What Facebook was in 2006 is very different (for better or for worse) than what it is in 2011. And it’s always a moving target.

But at least with Facebook, if you have the faintest idea of what you are talking about (which admittedly many don’t) you can only be so wrong. You can only be so far ahead or behind of a known target.

Not so with Google+.

You might look at Google+ and say “well, it’s just like Facebook, except that it’s got a slightly different privacy architecture, and it’s also just like Twitter, except the asymmetrical following has a different social substrate, and it’s just like Skype, so none of this is really new, they’re just all in the same place now.”

This argument is alluring. It’s also wrong. When all of these admitted analogues are in the same space it’s an entirely different dynamic. A jewelry store, a Burger King, and a Hot Topic are all distinct social spaces. Together, they’re a mall. And the sociology of a mall is not the sum of the sociologies of its stores. It’s something else entirely.

The same argument was made about Facebook in its early days (oh, it’s just photos + messageboards + email). It was wrong then. And it’s wrong now about Google+ – and it’s wrong exponentially. Facebook was a service built atop a combination of popular web standards. And Google+ is a combination of those services.

Google+ may yet flop. But I don’t think it matters if it does. It’s the first well-designed combination of all of these services. Whether or not it “kills Facebook”, it’s worthy of study and interesting on its own. I can’t remember the last time I was this excited about a change in the social media field. It’s going to be incredible to watch.

Users “Dislike” Facebook…More Than Banks?

by chris on Jun.30, 2011, under general

I mentioned in this blog post about how a lot of the excitement around Google+ seemed driven by a dislike of Facebook.

Well, according to a new study released by the American Consumer Satisfaction Index, Facebook is the 10th most hated company in America. It is hated somewhat less than the airlines and Comcast and somewhat more than (gulp) major investment banks.

I haven’t seen this study’s methodology. But it’s a striking finding.

Early Reactions to Google+ Early Reactions

by chris on Jun.30, 2011, under general

So I haven’t had an invite to Google+ go through yet, partially because of demand, partially because I think folks have been inviting me with my GApps account and Google+ isn’t compatible with that from what I see. But a lot of my friends have it, and have been talking about it on Facebook (very meta).

Before I go making any grand statements, I realize that my experience is limited and defined by my friends – specifically, my affinity group tends to overrepresent tech-savvy early-adopters.

Still, I’ve been stunned by the response to Google+. Seems like half of my friends already have it and are glowing about how great it is, and the other half desperately want in because they have been looking to leave Facebook.

My best friend Shane, like everyone else in our generation, was a ferocious Facebook user at first. But once things began getting icky three or four years ago, he changed his profile to this:

It’s still early, but I’m beginning to wonder if that alternative has finally arrived.

Finally Getting It

by chris on Jun.28, 2011, under general

Computerworld, on Google+:

However, what Google hopes will set its social network apart from Facebook and the smaller social networking services is that Google+ is set up to allow users to communicate within separate groups of their online friends. Instead of posting an update that goes out to everyone, Google+ enables users to create “circles” or groups, such as a user’s poker buddies, college friends, work colleagues and family members.Now a user can communicate separately with each group.

“The “circles” idea makes a lot of sense,” said Ezra Gottheil, an analyst at Technology Business Research. “It’s smart, and while you can do something similar in Facebook, it’s not Facebook’s main thing. It’s not as easy to do.”

You share different things with different people. But sharing the right stuff with the right people shouldn’t be a hassle. Circles makes it easy to put your friends from Saturday night in one circle, your parents in another, and your boss in a circle by himself, just like real life.

e: from the Times:

“In real life, we have walls and windows and I can speak to you knowing who’s in the room, but in the online world, you get to a ‘Share’ box and you share with the whole world,†said Bradley Horowitz, a vice president of product management at Google who is leading the company’s social efforts with Vic Gundotra, a senior vice president of engineering.

Architecture metaphors and everything!