Facebook’s Shadow Profiles

by chris on Oct.18, 2011, under general

Somebody is finallysuing Facebook about the shadow profiles they build of nonusers through importing users’ contacts and so forth.

Here’s hoping they take it down.

Facebook, J30Strike, and the Discontents of Algorithmic Dispute Resolution

by chris on Oct.15, 2011, under general

The advent of the Internet brought with it the promise of digitally-mediated dispute resolution. However, the Internet has done more than simply move what might traditionally be called alternative dispute resolution into an online space. It also revealed a void which an entire new class of disputes, and dispute resolution strategies, came to fill. These disputes were the sorts of disputes that were too small or numerous for the old systems to handle. And so they had burbled about quietly in the darkness – bargaining deep in the shadow of the law and of traditional ADR – until the emerging net of digitally designed dispute resolution captured, organized, and systematized the process of resolving them.

In most respects these systems have provided tremendous utility. I can buy things confidently on eBay with my Paypal account, knowing that should I be stiffed some software will sort it out (partially thanks to NCTDR, which helped eBay develop their system). Such systems can scale in a way that individually-mediated dispute resolution never could (with all due apologies to the job prospects of budding online ombudsmen) and, because of this, actually help more people than could be possible without them.

We might usefully distinguish between two types of digital dispute resolution:

- Online Dispute Resolution: individually-mediated dispute resolution which occurs in a digital environment

- Algorithmic Dispute Resolution: dispute resolution consisting primarily of processes which determine decisions based on their preexisting rules, structures, and design

As I said before, algorithmic dispute resolution has provided tremendous utility to countless people. But I fear that, for other digital disputes of a different character, such processes pose tremendous dangers. Specifically, I am concerned about the implications of algorithmic dispute resolution for disputes arising over the content of speech which occurs in online spaces.

In the 1990s, when the Communications Decency Act was litigated, the Court described the Internet as a civic common for the modern age (“any person with a phone line can become a town crier with a voice that resonates farther than it could from any soapbox”). Today’s Internet, however, looks and acts much more like a mall, where individuals wander blithely between retail outlets that cater to their wants and needs. Even the social network spaces of today function more like, say, a bar or restaurant, a place to sit and socialize, than they do a common. And while analysts may disagree about the degree to which the Arab Spring was faciliated by online communication; it is uncontested that whatever communication occurred did so primarily within privately enclosed networked publics like Twitter and Facebook as opposed to simply across public utilities and protocols like SMTP and BBSes.

The problem, from a civic perspective, of speech occurring in privately administered spaces is that it is not beholden to public priorities. Unlike the town common, where protestors assemble consecrated by the Constitution, private spaces operate under their own private conduct codes and security services. In this enclosed, electronic world, disputes about speech need not conform to Constitutional principles, but rather to the convenience of the corporate entity which administrates the space. And such convenience, more often than not, does not concord with the interests of civic society.

Earlier this year, in June 2011, British protestors launched the J30Strike movement in protest of austerity measures imposed by the government. The protestors intended to organized a general strike on June 30th (hence, J30Strike). They purchased the domain name J30Strike.org, began blogging, and tries to spread the word online. Inspired, perhaps, by their Arab Spring counterparts, British protestors turned to Facebook, and encouraged members to post the link to their profiles.

What happened next is not entirely clear. What is clear that on and around June 20th, 2011, Facebook began blocking links to J30Strike. Anyone who attempted to post a link to J30Strike received an error message saying that the link “contained blocked content that has previously been flagged for being abusive or spammy.” Facebook also blocked all redirects or short links to J30Strike, and blocked links to sites which linked to J30Strike as well. For a period of time, as far as Facebook and its users were concerned, J30Strike didn’t exist.

Despite countless people formally protesting the blocking through Facebook’s official channels, it wasn’t until a muckraking journalist Nick Baumann from Mother Jones contacted Facebook that the problem was fasttracked and block removed. Facebook told Baumann that the block had been “in error” and that they “apologized for [the] inconvenience.”

Some of the initial commentary around the blocking of J30Strike was conspiratorial. The MJ article noted a cozy relationship between Mark Zuckerberg and David Cameron, and others worried about the relationship between Facebook and one of its biggest investors, the arch-conservative Peter Thiel.

Since Facebook’s blocking process is only slightly more opaque than obsidian, we are left to speculate as to how and why the site was blocked. However, I don’t think one needs to reach such sinister conclusions to be troubled by it.

What I think probably happened is something like this: members of J30Strike posted the original link. Some combination of factors – a high rate of posting by J30Strike adherents, a high rate of flagging by J30Strike opponents, and so forth – caused the link to cross a certain threshold and be automatically removed from Facebook. And it took the hounding efforts of a journalist from a provocative publication to get it reinstated. No tinfoil hats required.

But even this mundane explanation deeply troubles me. Because it doesn’t matter, from a civic perspective, is not who blocked the link and why. What matters is that it was blocked at all.

What we see here is an example of algorithmic censorship. There was a process in place at Facebook to resolve disputes over “spammy” or “abusive” links. That process was probably put into place to help prevent the spread of viruses and malicious websites. And it probably worked pretty well for that.

But the design of the process also blocked the spread of a legitimate website advocating for political change. Whether or not the block was due a shadowy ideological opponent of J30Strike or to the automated design of the spam-protection algorithm is inconsequential. Either way, the effect is the same: for a time, it killed the spread of the J30Strike message, automatically trapping free expression in an infinite loop of suppression.

What we have here is fundamentally a problem of dispute resolution in the realm of speech. In public spaces, we have a robust system of dispute resolution for cases involving political speech, which involves the courts, the ACLU, and lots of cultural capital.

Within Facebook? Not so much. On their servers, the dispute was not a matter of weighty Constitutional concerns, but reduced instead to the following question: “based on the behavior of users – flagging and/or posting the J30Strike site – should this speech, in link form, be allowed to spread throughout the Facebook ecosystem?” An algorithm, rather than an individual, mediated the dispute; based on its design, it blocked the link. And while we might accept an blocking error which blocks a link to, say, a nonmalicious online shoe store, I think we must consider blocks of nonmalicious political speech unacceptable from a civic perspective. We have zealously guarded political speech as the most highly protected class of expression, and treated instances of it differently than “other” speech in recognizance of its civic indispensability. But an algorithm is incapable of doing so.

This is censorship. It may be accidental, unintentional, and automated. We may be unable to find an individual on whom to place the moral blame for a particular outcome of a designed process. But none of that changes the fact that it is censorship, and its effects just as poisonous to civic discourse, no matter what the agency – individual or automaton – animating it.

My fear is that we have entered an inescapable age of algorithmic dispute resolution. That we won’t be able to inhabit (or indeed imagine) digital spaces without algorithms to mediate the conversations occurring within. And that these processes – designed with the best of intentions and capabilities – will inevitably throttle the town crier, like a golem turning dumbly on its master.

This post originally appeared on the site of the National Center for Technology and Dispute Resolution.

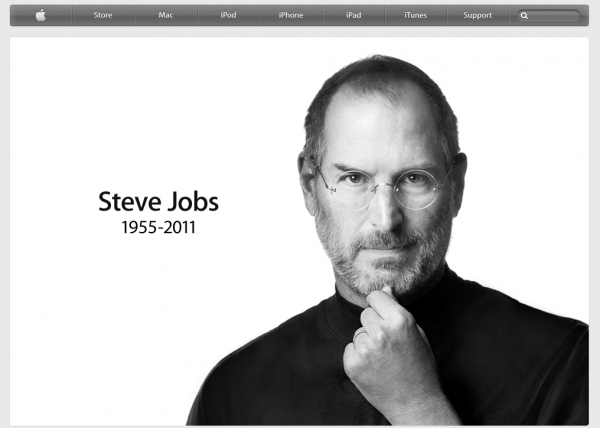

Steve and Me

by chris on Oct.06, 2011, under general

(the following is crossposted from the MITAdmissions blogs, for which I wrote it)

I remember the first time I ever saw a computer. I was four, and my family’s basement, which contained my father’s office, flooded during a terrible rain storm. My father, an electrical engineer who had swapped a soldering iron for a slim-cut suit and gotten into semiconductor sales, was wading around in the rising water, making sure that everything essential was stored on top of a tall cabinet out of harm’s way.

The very first thing he put up there was his treasured MacIIsi.

Later, I would come to love that MacIIsi for its games. Shufflepuck Cafe, Oregon Trail, Stuntcopter. I think for a time there I thought my dad must play fun games for a living, because that’s what the computer was clearly for. When I found out he used it for his job, I asked why. “Because,” he said, “it just works.”

And it did work. And even today, more than 20 years later, it still does.

I’ve always been a Mac guy. I don’t fall into the stereotype of the “Apple fanboy.” Neither does my dad, who is about as far as you can get from an artsy hipster farting around coffee shops and indie record stores. I always used Macs because, for me, they “just worked.”

Granted, some of this was because I grew up on Macs, and so I’ve always thought in Mac. I can make a Windows machine go, and I can bumble around a *nix system without breaking too much stuff. But on an Apple product, I find that I move about as skillfully and comfortably as if navigating my own kitchen. It’s like a native language: it’s not so much about whether you know the vocabulary and syntax as much as you understand, intutitively, how it operates, the innate and unspoken cultural references and use patterns.

To the extent that this is true – and to the extent that Apple products, from my Macbook to my iPhone, are omnipresent in my life – Steve Jobs was one of the most influential people in my life. Not because I knew him, or because I followed his dictums and philosophy. But because the technological environment in which I exist was created by him. If I were a fish, he’d have provided much of the water in which I swim.

When I was in college, I took a job working for Apple as a Campus Representative. During my second year Apple flew all of the Campus Reps to the Cupertino campus for training.

Cupertino was a strange, terrifying place. Everyone there lived very much in fear of Steve. No one ever joked, or even referenced, senior leadership. When some fellow reps made a skit which likely poked fun at Steve, they were threatened with expulsion from the program. All of the trainees watched, in a dark room a la the acolytes of Goldstein in the legendary 1984 Mac ad and with irony which apparently escaped Apple, a frankly cultish video about reproducing company culture. There was soft white light, ambient music, and Jonathan Ive speaking about how Apple was trying to make its stores seem like a church, a sacred space, where its followers would gather and share in the experience.

But it also showed, to a degree that can never be sufficiently told, how much Jobs’ vision guided Apple. He was truly a “visionary”, not only in that he was farseeing, but because he took that vision and was uncompromising in manifesting it in reality. Steve Jobs personally approved the design of the receipts in Apple stores. Not so much as a single pixel passed through the Apple environment without his approval.

Here’s a story Vic Gundotra – senior VP at Google – wrote about Steve’s devotion to design:

One Sunday morning, January 6th, 2008 I was attending religious services when my cell phone vibrated. As discreetly as possible, I checked the phone and noticed that my phone said “Caller ID unknown”. I choose to ignore.After services, as I was walking to my car with my family, I checked my cell phone messages. The message left was from Steve Jobs. “Vic, can you call me at home? I have something urgent to discuss” it said.

Before I even reached my car, I called Steve Jobs back. I was responsible for all mobile applications at Google, and in that role, had regular dealings with Steve. It was one of the perks of the job.

“Hey Steve – this is Vic”, I said. “I’m sorry I didn’t answer your call earlier. I was in religious services, and the caller ID said unknown, so I didn’t pick up”.

Steve laughed. He said, “Vic, unless the Caller ID said ‘GOD’, you should never pick up during services”.

I laughed nervously. After all, while it was customary for Steve to call during the week upset about something, it was unusual for him to call me on Sunday and ask me to call his home. I wondered what was so important?

“So Vic, we have an urgent issue, one that I need addressed right away. I’ve already assigned someone from my team to help you, and I hope you can fix this tomorrow” said Steve.

“I’ve been looking at the Google logo on the iPhone and I’m not happy with the icon. The second O in Google doesn’t have the right yellow gradient. It’s just wrong and I’m going to have Greg fix it tomorrow. Is that okay with you?”

Of course this was okay with me. A few minutes later on that Sunday I received an email from Steve with the subject “Icon Ambulance”. The email directed me to work with Greg Christie to fix the icon.

…

But in the end, when I think about leadership, passion and attention to detail, I think back to the call I received from Steve Jobs on a Sunday morning in January. It was a lesson I’ll never forget. CEOs should care about details. Even shades of yellow. On a Sunday.

Jobs was not without his faults. As I said earlier, the Apple environment could be cultish. He could, according to popular accounts and to others I knew at Apple, be a real jerk to employees in pursuit of his vision. He most certainly stabbed Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak in the back several times. Just one example from Rotten.com’s biography of Woz:

When Steve Jobs worked at Atari, the company was working on creating the arcade game Breakout, which required 80 Integrated Circuits (ICs). The less ICs there were, the cheaper the games would be to produce, so Nolan Bushnell (Atari’s president) offered $100 for every IC that could be knocked out of the design. Jobs brought Woz the challenge, and over four days and nights at Atari they put together a design that only required 30 ICs. Bushnell gave Jobs his $5000 bonus, which Jobs “split” with Wozniak by telling him it was a $700 bonus, giving him “half,” or $350. Woz was delighted, but years later found out the truth. And cried.

He quite publicly cut corporate charity from Apple entirely. The production conditions at Foxconn and elsewhere are terrible. In these respects, Jobs was perhaps no worse than any given industrial magnate. But that’s an incredibly low bar to trip over, and he was certainly no better.

The legacy of Jobs, however, will not be the terror he was as a boss, or the degree to which he hamstrung developers with capricious censorship in the App Store, or even the degree to which he was ruthless in his pursuit of production.

It will be the fact that he possessed an unmatcheable unifying vision. It will be all of the times he saw what the market wanted before the market did. It will be the fact that his devotion to something as simple as typography completely changed the way people thought about user experience on personal computers. It will be the fact that for decades past – and maybe decades to come – Apple has consistently produced technologies that have changed the way the personal computing world works. It will be the recognition that user experience and a devotion, above all else, to good design, matter. And it will be his uncompromising – to a fault – dedication to making things that “just work.”

Like it or not, Steve Jobs changed our world. And now he has left it.

And I will miss him.

Frictionless Facebook

by chris on Sep.27, 2011, under general

pkoms sent me an editorial today from ThisIsMyNext by Laura June on the subject of “frictionless” sharing in the context of the new Facebook Timeline feature.

Excerpts:

The feature that I find most unsettling, however, is the connection which Facebook now has to applications such as Rdio, a streaming music service which already served as a type of social network: you can have friends and followers, and share your listening habits in a closed off network. Rdio is a tiny service compared to Facebook, but was already connected with it, and had the ability to share a song with the click of a button whenever you wished.

…

[The] one way I actually enjoyed using Facebook was to share, via Rdio’s little sharing button, a song or two a day, posted to my wall. To be clear, sharing that song was always a conscious choice, based on numerous other little choices I made within the blink of an eye: what time of day is it? How am I feeling? Have I shared this same song before? In effect, I was “saying something†with my click.

The new relationship between Rdio and Facebook — based on the nefariously named Open Graph which debuted last year — is one of “frictionless sharing.†What this means is that the same act of connecting my Facebook and Rdio accounts now presents me with only one real option: I will now share every song I listen to, automatically, via the news ticker on the right column of the Facebook dashboard, with every single one of my friends (or customized groups).

What we see here is a manifestation of the ideology of radical transparency and its effects on privacy-as-performance, performance-constituting-contexts.

Put more concretely:

Ms. June used to consciously choose which songs to share. She chose based on a variety of social cues, but always with some level of (sub)conscious awareness of the message the sharing of the song would send. And through each decision to share or not to share, she constructed her identity at that time, by arranging her data as a social performance.

Now, however, the process is automated. She can either choose to opt-in to all of the service, or opt-out of all of it. Granularity – temporal granularity anyway – is not an option.

If this example seems trivial – who cares about music choices? – take the principle and move it laterally to a parallel hypothetical. Facebook currently gives me the option to share any website I visit with my Facebook friends. I click a share button and it populates my News Feed. This is something I love about Facebook. In fact it’s one of the few reasons I still use it. It’s building a less-robust del.icio.us service into my social network. And I know a lot of people who use it.

Suppose, though, that you’re someone who loves the Share functionality. What if Facebook were to simply change the structure so that it automatically published, in your News Feed, every website you visited?

It’s perfectly technologically possible. Unless you take pains to block it, Facebook already tracks every website you visit that has a ‘Like’ button on it. They could very easily add this functionality to a published News Feed.

Now Facebook would have to be insane to do this, because the uproar would be fantastic. But here is the question: why would the uproar be fantastic? Isn’t the ideology of radical transparency in play in the Rdio example in play here? Sure, the spectrum of content might be different, but the mechanics of information dissemination – whether or not you have an affirmative role to play in constituting your identity, or whether it is automated – are identical.

Fine With This As My Epitaph

by chris on Sep.26, 2011, under general

I just returned from NACAC, the conference for college counseling and admissions professionals. I was there to sit on a panel about advanced social media use in higher education.

The Choice Blog in the NYT quotes me thusly:

Other institutions have remained selective in their social media use. “We don’t use Twitter,” Chris Peterson, admissions counselor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said dryly. (The school is active on Facebook, though.)

I think (I hope) I said a lot of other good things too. But I’m quite happy with this droll skepticism defining my contribution to the conversation.

Facebook’s Timeline

by chris on Sep.23, 2011, under general

So Facebook has announced a redesign.

The update, as I understand/conceptualize it, consists of two elements.

One element is a redesign of the user’s profile aesthetically. This is known as “Cover”. The user profile now has a big banner image, a small mugshot, and two columns of content along the page. I like Cover a lot. It’s a much more visually appealing use of the space. Feels very modern and clean.

The other element is “Timeline.” As I understand it, Timeline works by allowing your friends to basically experience highlights of your time on Facebook by scrolling back chronologically.

Here’s their video demonstrating it:

I think Timeline in many ways represents my biggest privacy fears about Facebook. I’ve written a lot about Facebook has collapsed the spatial contexts that define social situations; now, it’s launched an assault on the chronological contexts as well. Of course, it was always possible to just click through the bottom of a user’s page to see old wall posts, or to photostalk into history. But it wasn’t this simple, and degree of difficulty means everything in this space.

I’m still trying to sort my thoughts out about this, and this blog post is as much about organizing my thoughts as anything else. But I am coming to think that there is a trend across Facebook design decisions, and that trend could be loosely characterized as follows:

In the beginning, Facebook essentially served as a platform for establishing and maintaining weak ties. Not only was the technology not nearly as advanced as it is now, but the audience – remember, limited to just college students – was also very thin. Both the simple technology and the thin potential audience meant that it was pretty difficult to collapse contexts, because the limitations of the space and audience effectively (not identically) worked like the informational constraints of the real world.

As time has gone on, both of these things have changed. One thing which has changed is the fact that Facebook is now delivered to a much broader audience. And the other thing which has changed is that the technology now supports a much deeper interaction among members of that audience.

This Wired interview with Chris Cox, Facebook VP of Product was very informative:

Cox says that instead of that brief conversation you used to get by scanning the previous version of the profile, visiting the profile will be the equivalent of going to a bar to have a long overdue five-hour soul exchange. “It’s that conversation where you play the jukebox till it runs out, the bar closes, and you walk about and say, ‘Man, that was really deep,’†he says.

But here is the thing. There are a lot of people with whom I am friends on Facebook that I would not go into a bar with five hours and bare my soul to. That is not what Facebook was historically for, and I don’t think that’s how most of its users want it to work.

Cox’s conception of Facebook is as if it were connecting a bunch of people with strong ties. And it is true that I am Facebook Friends with my very best friends in the world. But it is also true that there are 600 people with whom I am Friends that I like maintaining loose contact with but wouldn’t bare my soul to.

When you think about it this way, it’s a striking transformation. What began, by design and audience, as a social utility intended to facilitate the maintenance of weak ties has become, by design and audience, a social utility built around profound sharing with supposedly strong ties. It’s a complete overhaul of the entire social ecosystem, and a complete reversal of Facebook’s mission and role in people’s lives.

Still trying to think through all of the implications of this, and would love to hear other’s thoughts as well.

Anonymous’ Laywers: DDoS == Sit-In

by chris on Sep.20, 2011, under general

Such is not the case for lawyers representing some of the script kiddies who compose Anonymous, who told Talking Points Memo that:

Stanley Cohen, representing 20-year-old Mercedes Haefer on a pro-bono basis, told TPM that he got involved in the case because he didn’t like the way the feds were dealing with Anonymous.“I think this is a political persecution, end of story,” Cohen said. “This administration wants to send a message to those who would register their opposition: ‘you come after us, we’re going to come after you.’ That’s what has happened in the Eric Holder Department of Justice.”

“When Obama orders supporters to inundate the switchboards of Congress, that’s good politics, when a bunch of kids decide to send a political message with roots going back to the civil rights movement and the revolution, it’s something else,” Cohen told TPM, stipulating that he was not indicating that his client was even involved. “Barack Obama urged people to shutdown the switchboard, he’s not indicted.”

“It’s not identity theft, not money or property, pure and simple case of an electronic sit in, at best,” Cohen continued.

Facebook Launches Improved Friends Lists

by chris on Sep.13, 2011, under general

Title says it all. Via Facebook Blog:

Lists have existed for several years, but you’ve told us how time-consuming it is to organize lists for different parts of your life and keep them up to date.

To make lists incredibly easy and even more useful, we’re announcing three improvements:

- Smart lists – You’ll see smart lists that create themselves and stay up-to-date based on profile info your friends have in common with you–like your work, school, family and city.

- Close Friends and Acquaintances lists – You can see your best friends’ photos and posts in one place, and see less from people you’re not as close to.

- Better suggestions – You can add the right friends to your lists without a lot of effort.

And so on and so forth. Not a lot of commentary from me here – we’ll have to see how it rolls out. But I spent enough time criticizing Facebook: it’s only fair to note when they are at least trying to do something right.

I remember when Friends Lists were launched. It was early March 2008, and I was out at Facebook visiting a developer friend. Their launch inspired my thesis. Three years later they are finally being put to the purpose I hoped they would.

It’s not perfect, even if implemented as Facebook has described. But it’s a start.

Pretty Much Sums It Up

by chris on Aug.27, 2011, under general

via @placito:

“Why do people care so much about Steve Jobs resigning?” he said as he typed on a square of glass that contained all the music he ever owned