Knowledge Unbound

by chris on Oct.25, 2012, under general

What is a textbook? Where does it come from? How does it work?

For a long time these questions would have been easy to answer. A textbook contains information about an academic subject, such as “An Introduction to Economics.†Textbooks are written by professors at the behest of companies which then sell them at usuriously high rates to all students being introduced to economics that semester. Professors assign, and students buy, textbooks in the hope that by progressing through them the student will learn the material.

The online education startup Boundless intends to disrupt this dynamic. The founders of Boundless realized that many introductory textbooks share the same core concepts, and much of the substance of that information – like equations or elements – lies in the public domain. While textbook manufacturers incurred significant overhead by producing and distributing heavy paper books, Boundless could simply make much the same content available through the web at markedly lower marginal costs, undercut the manufacturers, and educate the world.

But what should go in these digital volumes? Boundless decided to mimic the structure and topics of common textbooks. If most versions of “Introduction to Economics” opened with a discussion and explanation of GDP, then Boundless would too, with the same (public domain) equations wrapped within slightly different explanations. It would thus offer students equivalent versions of their expensive textbooks for free.

A group of textbook companies sued Boundless. Their complaint, filed in the Southern District of New York, alleged that Boundless impermissibly copied “the distinctive selection, arrangement, and presentation of Plaintiffs’ textbooks.” “The choices made by Plaintiffs and their authors,” they argued, “are by no means basic, mechanical, routine, obvious, standard, or necessary for textbooks on those subjects…[but are] expression[s] of their unique and highest pedagogical aspirations.”

The ink on the complaint was barely dry before Boundless pivoted its business model in response. Rather than produce equivalent versions of popular textbooks, Boundless announced it would make available “all knowledge” on a particular subject for students to access as needed. Instead of building a digital textbook which students could read on a screen, Boundless would build a digital pool of information into which students could dip as and where they needed, sidestepping entirely the claim of copyrighted editorial activity.

Boundless’ aim to make available “all knowledge” on a particular subject is obviously nonsense, but it is nonsense for interesting reasons. Investigating why and how it is nonsense reveals the role that the properties of media play in the production of knowledge.

Boundless’ mission to make “all knowledge†available compels us to immediately ask: what is “all knowledge†of economics? Where does it live? And how do we know when we’ve gotten it bound up and bottled?

But these questions, important as they are, are not the first questions we would have asked of a company which aimed to make “all knowledge” available in a physical textbook. Instead, we would have asked: How many volumes? Where will you get all of the paper? Where will the books be stored? And how will people get through them?”

The material characteristics of books – above all the marginal cost of additional pages – concealed somewhat the politics of knowledge production, or at least displaced them to a concern of the second order. No one would ask why a textbook manufacturer didn’t include everything about economics in a single volume (or, by extension, what “everything about economics” even meant) because a volume which contained it would be useless for anything besides a very large doorstop.

To be sure, different editors offer different definitions of what constitute the core concepts within textbooks. After all, if there were no competition about what constitutes “Econ 101” the textbook companies couldn’t sell competing versions. But the outer reaches of a field remain, by material necessity, largely unexamined and unexplored. If a textbook is materially constrained to 300 pages there may be bitter battles over pages 298-302. “Page†768, though, will be utterly irrelevant since it will never be printed, and so its possible contents remain uncontested.

A textbook, viewed in this light, is not a product as much as an an fossil: sediment deposited at the bottom of a river of editorial judgments, which eventually takes its form apart from that which formed it. But Boundless has no page limits: Boundless could, from a technological perspective, be knowledge in motion, knowledge in process, knowledge unbound by the constraints of books. It is only after we have cleared these technological hurdles that we become lost in the fuzzy, shifting spaces created by questioning where and when knowledge ends.

These questions are unsettling and unanswerable, not only for the engineers at Boundless, but for the textbook manufacturers, who attempt to substantiate the value of their editors’ contributions by appealing to the authority of institutional affiliation. It is for this reason that, whether or not they succeed as a business model, we owe Boundless an intellectual and epistemic debt. By forcing us to imagine academic information floating free of material limitation, they have revealed just how confused, contradictory, and contingent the production and organization of information and education really is.

This entry adapts an essay for FAS 297 at Harvard and originally posted on the blog of the Center for Civic Media.

The Politics of Verifiability

by chris on Oct.16, 2012, under general

In “Too Big To Know”, David Weinberger correctly characterizes our pressing epistemic crisis. How do we know what we know what we know on the Internet? How do we create, locate, and trust that authority?

As Weinberger points out, the authority of print publications is in part conferred by the metadata of material scarcity. The cost of producing and distributing marginal copies of Nature tells us that someone must have had good reason (and backing). Material capital precedes reputational and social capital. As Clay Shirky has put it, in a world of print, the dynamic is filter, then publish; on the web, it inverts to publish, then filter.

Weinberger correctly notes that this epistemic crisis has always been with us. Knowledge always has been a social construction; what is true, and what is false, is what defines (and is defined by) a culture. The shift in material limitations has merely revealed the contest of construction. But the process of construction also changes when it shifts from the darkness to the light. What are the politics of this new age of knowledge construction?

Consider the case of Wikipedia. The author Philip Roth recently wrote in the New Yorker about opposition he encountered while revising an article about one of his books. Wikipedians reverted Roth’s edits on the rationale that his word alone was insufficient evidence. When Roth argued he, as author, was the last best source for information about his book, he was told that Wikipedia was not a repository for what was true, but rather a repository for what was verifiable.

Those who celebrate unreliable readers and the death of authorial intentionality were no doubt charmed by this response (and the subsequent revelation that Roth’s edits may have been wrong on the merits). But their pleasure may be premature. To paraphrase the Marxist critic David Harvey, Wikipedia never solves its authorial problems, it just moves them around geographically.

When Wikipedia says that it seeks not what is true, but what is verifiable, it does not actually discard truth. Instead, it disguises the idea of truth behind the mask of verifiability. Rather than rejecting authorial intent, it merely relocates it, by distributing it more generally.

This conflict can be seen in a close reading of the Wikipedia:Verifiable page. Wikipedians have struggled (admirably) with the difficulty of defining “reliability” in sources. Many of its considerations are legacies – almost intellectual skeumorphisms – from an era of costly printing, as when Wikipedia characterizes “self-published” material as “usually unreliable” because anyone can do it. Instead, Wikipedia admonishes its editors to rely on “established expert[s] on the topic of the article, whose work in the relevant field has previously been published by reliable third-party publications.” How do we know when a source is reliable? When it has already been reliable; which is to say, when it’s reliable all the way down.

Of course, there are exceptions to the reliability rule, and these come in the area of explicit opinion. Where criticisms and opinions are concerned, these need not come from established institutions. After all, it is verifiably correct that some Americans believe President Obama is a Muslim, and we can cite the primary sources to prove it.

This is where the politics of verifiability become more interesting. As the blogger Jay Rosen has noted in his commentary of the present Presidential campaign, the uncritical passing-along of statement is not a neutral act. A press which strives for an independent “truth”, as epistemically incoherent as that may be, will come to very different results, with very different effects, then a press which simply passes along statements which it can verify a campaign uttered.

As Rosen has pointed out, this dynamic can be gamed in different and interesting ways. For example, a clear substantive distinction (for example, whether to transform Medicare into a voucher system or preserve it more or less in its present form) can become deeply muddied, as when both campaigns accuse the other of planning to end it. But this muddiness is not neutral. The equal-but-opposite claims to “end Medicare” removes the policy differences from their pedestal and submerge them deeply in the muck of partisan squabbling. A potentially defining difference becomes recast as “just more partisan squabbling.” This displacement benefits whichever campaign would have “lost” a debate on the merits of plans by disarming its opponent of an advantage.

This is not to say that the consensus-driven (and driving) era of evening newscasters speaking in unison was some panacea. The “truth” then was just as false as it seems now; we are just able to imagine (unable to avoid seeing?) otherwise in an Internet era. The point is that verifiability has a politics too, a politics which both relies on some sites of traditional authority while it dismantles or dislocates others.

This entry adapts an essay for FAS 297 at Harvard and was originally posted at the Center for Civic Media.

How Does Technology Work?

by chris on Oct.01, 2012, under general

I have recently spent a great deal of time thinking about technology. This may come as no surprise. After all, I am a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, working in a lab which makes civic technology, and writing my thesis about how people use social technology.

But though I spent my day surrounded by and studying about technology, what I’ve been struggling with is a somewhat deeper and more difficult question: how does technology work?

By this, I do not mean how does it mechanically or electronically work, which is to say how pulleys move or how bits flow. Rather, I have been trying to figure out how technology does the work it does – or perhaps appears to do – in the world.

Please forgive my tortured phrasing. It comes from stepping very carefully around several conceptual landmines.

For example, I could – and once would – have simply said “how technology affects or changes the world.” But this presumes, or at least implies, that technology does have an affect or agency independent of the people around it.

This presumption, if formalized as theory, is called technological determinism. At the risk of further reducing a reductive theory, the strong form of technological determinism basically says that certain technologies drive history in directions as if by their own accord and apart from the conditions into which they are introduced. Technologies are like medicines which, once injected into the patient, have predictable and uniform effects. Some peg Marx as a technological determinist when he argued “the handmill gives you society with the feudal lord: the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist” and “modern industry, resulting from the railway system, will dissolve the hereditary divisions of labor, upon which rest the Indian castes, those decisive impediments to Indian progress and Indian power.” The ideology of technological determinism underlies those who believe the printing press inevitably led to the democratization of Europe, and who believe that the Internet inevitably leads to the democratization of the world.

Roughly opposed to the technological determinists are the technological constructivists. Constructivists would argue that the printing press, rather than driving democratization in Europe, was instead mustered towards that end by Europeans. The press’ apparent effects were cultural contingencies, not technological inevitabilities, which is why the invention of the printing press had different results in the East than in the West. If strong determinists argue that technology shapes the world, strong constructivists argue that the world shapes technology.

Perhaps because these are strong arguments, and thus meant more for intellectual provocation than accurate description, I am satisfied with neither.

This is what I meant when I said I had been struggling to understand how technology works.

It seems clearly counterfactual that technology has inevitable effects, as we see in the divergent cases of the printing press. But neither does it seem so simple to me as that people somehow choose to shape technology to their clean, preexisting will. When I said in seminar a few weeks ago that I felt that somehow technology had some agency or effect which operated outside of individuals, a perplexed classmate asked me “well, how would that work?” I confess don’t know. But then, I don’t understand how individual agency is supposed to work either.

I still don’t know how technology works. But I think I might have some sense of the outlines of an explanation.

Let me illustrate something of what I mean. Consider the technology of a highway. A highway allows people (when equipped with certain modes of transport) to travel long distances comparatively quickly. As such, it enables, among other things, certain commuting patterns, and thus patterns of living.

I grew up in the southern New Hampshire exurbs. My family wanted to live in a relatively rural setting, but my father’s job was in the Lowell area. Without highways, commuting from Lowell to southern New Hampshire would have been prohibitively costly for most people. With highways, it was very manageable.

Highways (and cars, and cheap gas, and rural telephony, and everything else that goes into living in the exurbs) were socially constructed technologies. They were produced by people who hoped to achieve particular ends.

But the type of life enabled by highways also affected the people who lived those lives. When I was growing up I loved living in a semi-rural environment. That love influenced my perspective, my goals, and the sorts of technologies I wanted to see in the world (like high speed rail to rural places). But my love of that environment was only made possible by the highways which preexisted me, because the world they made possible was a world I liked living in and wanted to reproduce.

McLuhan says somewhere that “we shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.” As was so often the case, the Oracle of Ontario speaks in aphorisms that are sexy but simplistic. We are shaped by our tools, but we also reshape them, and this is an ongoing process. It is an interaction, not an action. But how does that interaction work?

I would like to suggest that technologies do not have effects, nor are they effected upon. Instead, their design characteristics offer certain frameworks of compliance and resistance. These frameworks are used by people, but they are not totally subordinate to people. A hammer can do many things (drive a nail, stop a door, kindle a fire, bang a gong), but its features enable (or, in the language of design, “afford”) certain uses, and through that enablement continue to suggest uses, and by extension ways of thinking and seeing the world.

I don’t think this is mysticism, or that I am imbuing a hammer with some magic power. This theory is, instead, born of a deep skepticism about the magic which supposedly allows individuals to be the autonomous agents in their own lives.

This framework of compliance and resistance is how I’ve come to think about the interaction of people and technology. Of course, saying “it’s complicated, it’s messy, and it depends” isn’t the sharpest analytical tool in the shed. But I feel like it helps me muddy towards the truth.

This post originally appeared on the blog for the Center for Civic Media

Always Already Mediated: The Myth of the Great Agora

by chris on Sep.17, 2012, under general

I am presently cross-registered for a class at Harvard called Digital Power, Digital Interpretation, Digital Making. Taught jointly by an impressively interdisciplinary array of professors, it is, to paraphrase a characterization from the first day of class, an intentionally incoherent but hopefully productive approach to thinking about all sorts of issues bound up in our digitally mediated world.

Our first full seminar occurred this afternoon, led by Professor Jonathan Zittrain. It was a brief history of the Internet, or more specifically a study of the Internet and how it took shape, looking not only to significant individuals (Jon Postel) and organizations (IETF), but also practices (RFCs), contingencies (common carriage), and conflicts (the birth of ICANN).

Our reading, for this class, included two seminal papers by Yochai Benkler and Larry Lessig. Each deals with the question of what the Internet is and contains a vision for what it might be. Each deals deeply with the structure of the Internet. But there is a very interesting tension between the two when it comes to thinking about how people are mediated generally.

In From Consumers to Users, Yochai Benkler advocates for an Internet organized around the commons in order to promote an information environment constructed of”diverse and antagonistic sources.” He does so by repurposing a central metaphor of the IETF – the hourglass of layers of Internet protocols – to describe layers of infrastructure: the physical, the logical, and the content. After revealing the material characteristics of the Internet, he discusses the implications of private vs. commons ownership and administration. Benkler strongly favors the latter. “Today, as the Internet and the digitally networked environment present us with a new set of regulatory choices, it is important to set our eyes on the right prize,” he writes. “That prize is not the Great Shopping Mall in Cyberspace. That prize is the Great Agora—the unmediated conversation of the many with the many.”

I am a big fan of Benkler, of his many-layered model of the Internet, and of the commons argument generally. However, this last line struck me, because I don’t think it makes any sense.

Consider Benkler’s ideal of the Great Agora. Presumably, he means an ideal version of the Greek agora, or central, open-air gathering space in the ancient Greek city states, which, Benkler says, was home to “the unmediated conversation of the many with the many.”

But such a space was profoundly mediated. Most fundamentally, from the perspective the study of media, it was mediated by the architecture of the Agora. By this not I mean only its literal architecture (walls, pillars, stalls, and so forth). I mean also the informational properties of the physical world within which the Agora is situated, and upon which all other behavior necessarily depends.

For example, one property of conversation in the Agora is that sound travels until it does not. The ability to raise or lower the volume of ones voice to adjust for audience (or the inhibition posed by an inability to adjust volume for the intended audience) is a natural, taken-for-granted property of the physical world which mediates the conversations those in the Agora would like to have. And there are social practices which are organized around manipulating – one is tempted to say “hacking” – these properties, whether it is huddling together in hushed tones in an attempt to limit a message, or organizing a human microphone in order to spread it further.

This insight developed for me (and was explored further in my thesis) after reading the works of Larry Lessig, in this case his The Law of the Horse: What Cyberlaw Might Teach. In his attempt to demonstrate that cyberspace “is” nothing – that it “is” only what we build it to be – Lessig describes the importance of such architectural (that is, built) considerations with the following example:

We have special laws to protect against the theft of autos, or boats. We do not have special laws to protect against the theft of skyscrapers. Skyscrapers take care of themselves. The architecture of real space, or more suggestively, its real- space code, protects skyscrapers much more effectively than law. Architecture is an ally of skyscrapers (making them impossible to move); it is an enemy of cars and boats (making them quite easy to move).

This is not to say that the medium determines what is said, but only to say that it affects how what is said is said, circulated, and accessed. As Saenger writes, until the invention of spaces between words, texts were almost always read aloud, because only by sounding out the phonetic structure of the mass of letters could words be parsed. Or, in the case of the human voice, the ability to be heard in the metaphorical sense of understood depends on the ability to be heard in the literal sense of sound waves moving through the medium of the air.

All of this is to say that when we study how people communicate amongst each other, we can’t compare our analyses or advocacies against idealized abstracts of “unmediated” individuals. There is no – and could never be – such a thing as an “unmediated conversation of the many with the many.” We are always already mediated. Any such study of how people communicate must be grounded in what the properties of a given medium are and how individuals interact with these characteristics to achieve their ends. Benkler has already done a terrific job of this with his deep dive into the material characteristics of the web, but it’s important to remember for apparently “unmediated” environments too.

This post originally appeared on the blog for the Center for Civic Media.

Blogging the NAMAC Panel: Public Enemy and Private Intermediaries

by chris on Sep.08, 2012, under general

I’m blogging from Minneapolis, Minnesota, at the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture (NAMAC) conference Leading Creatively 2012, where I’m representing the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC).

Earlier today I presented on a panel entitled Digital Frontiers: Copyright, Censorship, the Commons, and Privacy. The panel description read:

Can freedom of the press and the right to know survive the rough-and-tumble politics of lobbyist-addled Washington? Is your mobile device secure from search and seizure over whatever content you load onto it? Will the documentary feature you’ve labored over be accessible to your target audience? The Digital Frontier is up for grabs — and your participation in the debate will make a difference.

The panel was moderated by Nettrice Gaskins, President of NAMAC. Also on the panel were Chris Mitchell, Director of the Telecommunications as a Commons Initiative at the Institute of Local Self-Reliance, and Hank Shocklee, sonic architect, President of Shocklee Entertainment, and cofounder/producer of Public Enemy.

Nettrice presented our panel with five questions. Each of us had the opportunity to speak or pass on each. After 45 minutes, we broke out into small groups for in-depth discussions of each question.

The questions were:

Creation Question

What happens when technology democratizes the technique and the attitude and the method of creating? AND What happens when anybody can be an artist?

Copyright Question

Regarding remixing Lawrence Lessig implies here that attempts to regulate copyright online will kill creativity (innovation). What is your response to Lessig’s argument (explain why)?

The Commons Question

What impact do you think commons-based peer-production, driven by new and emerging technologies will have on independent media organizations?

Privacy Question

What measures do you think need to be taken to better guarantee anonymity?

Censorship Question

What is your compelling argument to legislators and big media corporations who embrace censorship and are willing to sacrifice peoples’ civil liberties in their attacks on free knowledge and an open Internet?

I spent most of my time on this last question, and I thought I’d share some what I had to say here.

One of the things that makes both studying (and fighting) censorship in the 21st century so interesting (and difficult) is the ways in which it confounds traditional regulatory frameworks.

For most of the 1900s, if you asked a civil libertarian to describe the evils of censorship, she would have likely told you about governments trying to restrict or obstruct free speech and the flow of information. The National Coalition Against Censorship, for example, was founded in the wake of New York Times v. U.S., the “Pentagon Papers” case.

Battling government censorship is, in my opinion, a noble cause. It is also relatively straightforward.

The First Amendment provides a fairly robust framework for fighting government restrictions on speech. When viewed through the lens of the preclassical legal consciousness which dominated at the time of the Founding Fathers, the Amendment may be understood as being produced by, historian Elizabeth Mensch writes, “a Lockean model of the individual right holder confronting a potentially oppressive sovereign power.” The classical legal consciousness which followed only further developed the public/private dichotomy in law, conceiving of each as separate “spheres” properly kept separate, leading, eventually and perhaps inevitably, to a fetishization of contract and the Lochner era.

Without going too much further into an unnecessary analysis of legal history, the point is that our legal, political, and conceptual models all allow us to grasp what is at stake when a government censors speech. We may (and often do) disagree over the meaningful margins of the argument – when / if / what / how a government may intervene in expression – but it is an argument which is intellectually intelligible to anyone steeped in America’s brand of liberal theory.

Things become much murkier, however, when private intermediaries get in the game. The First Amendment doesn’t govern what companies do, and the American tradition of obeisance to contract tells us that when we use an information service we must take the bad with the good or take our business elsewhere.

This matters because there is a rapid expansion of privately owned speech intermediaries. Facebook, YouTube, Google: if you use it to communicate to an audience, then it is probably privately owned and administered.

Let me give a recent example. Josh Begley is a graduate student at the Integrated Technologies Program at NYU. Last month, Josh made an iPhone app called Drones+. Drones+ aggregated reports of drone strikes by the U.S. military and put them on a map, pushing notifications to its users whenever the American military bombed someone with an unmanned drone.

According to Wired, Apple has now rejected Josh’s app three times. First, because it was “not useful”; then, because of a misplaced logo; and finally (and most recently) because its content was “objectionable and crude.”

Imagine, for a moment, that this were a U.S. government agency trying to enjoin the distribution of a freely available computer application which did the same thing. People would go nuts. And they would go nuts because it would be seen as an unacceptable overreach of government authority in contravention of the First Amendment. But while Begley’s story certainly made news, he hasn’t been able to enjoin Apple, because Apple is under no obligation to publish his app.

This is the central struggle of anti-censorship activists in the digital age. Our speech is moving into private spaces, but the mental models which provided protection are unable to follow it there. The only thing activists can do to companies like Apple and Amazon is shame them by invoking and relying upon a generally distributed sense that people should be able to say what they want within poorly defined parameters. That’s a scary thought for people who believe in the free flow of information, but until we develop a framework which allows us to understand and respond to censorship within private intermediaries, it’s the only option we have.

This post was published originally on the Center for Civic Media blog here.

LinkedIn and Facebook Are Different (For Me)

by chris on Aug.25, 2012, under general

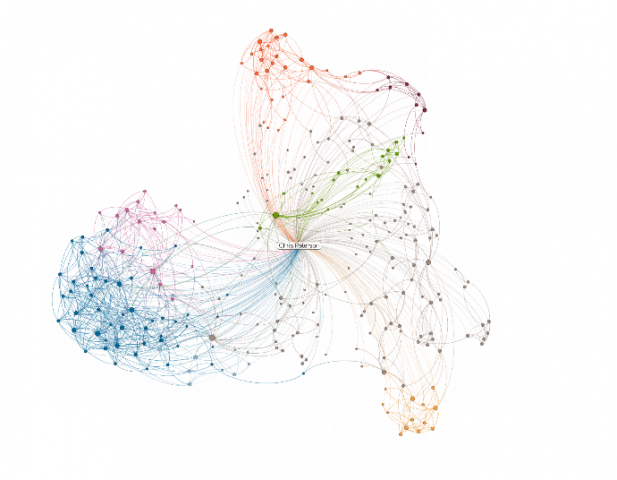

@mstem clued me in to LinkedIn’s new “InMaps” feature, which allows you to visualize your LinkedIn network:

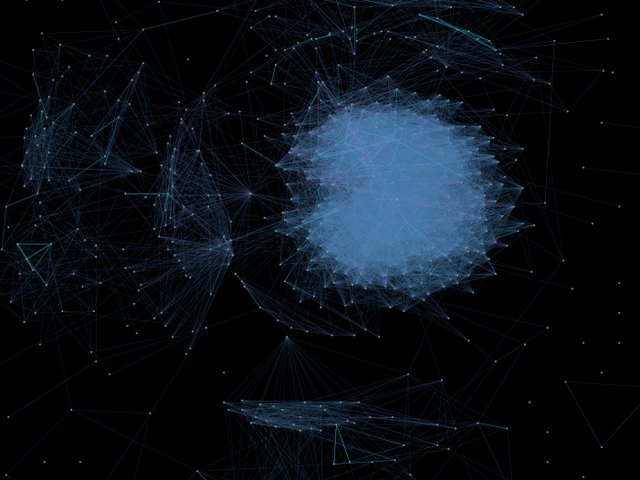

Most striking to me was how my LinkedIn network differs topographically from my Facebook network, generated a year or so ago by the Nexus application:

For most people, social network sites are constituted and animated by the social networks which preexist them in the physical world. The sites themselves merely shape the contours of these networks as they are represented in those spaces. Fascinating for me to see visually what I already new intuitively: that despite both being “social network sites”, LinkedIn and Facebook are very socially for me.

What Is A “Truth Team” And How Does It Work?

by chris on Jul.12, 2012, under general

The following image has been popping up in my News Feed:

The image was published by the “Obama Truth Team”, a Facebook page operated by the Obama for America campaign. It has been shared over 5,500 times in under an hour.

I am a progressive. I have no particular affection or sympathy for Mitt Romney. But there are a few things about this image that make me feel kind of uncomfortable.

There is something unsettlingly Orwellian to me about a political organization – never mind a Presidential campaign – referring to itself as a purveyor of “truth.” Sure, all truths are contested and constructed, but some more than others, especially in certain contexts. Point number 3 refers to the “truth” that Romney owned a “questionable” shell corporation. Who is doing the questioning here and why?

Forget, for a moment, the other problematic assertions in here (Point 4 is just “Kerry seems French!” inverted). We have a narrative, embedded in an image, which claims as truth a questionable-ness.

Even stranger, to me at least, is the page’s own description:

The Truth Team is a grassroots network of people dedicated to debunking the GOP’s myths and getting out the facts about President Obama’s record. This page is run by Obama for America, President Obama’s 2012 campaign.

(emphasis mine)

A grassroots network is, by definition, not run by a national campaign. It could be another type of network, a network which emanates from a central hub and functions to disseminate messages, like a nerve system.

Most interesting, though, is the whole dynamic of this operation.

To me, a “Truth Team” conjures up memories of “street teams” from the late 1990s and early 2000s: fans of bands, tapped to serve as foot soldiers in publicity campaigns. And I think the Truth Team is running on the same kind of mojo. It’s just a lot of fans, taking these images from the campaign and then retransmitting them as a mindless transaction, a sort of thoughtless, head-nodding “yes-and” post and repost and repost as a message mushrooms through a medium.

I want to be clear that I’m not accusing Obama supporters of being mindless or duped or anything (certainly not any more so than any other blind partisan). I just think there is something very interesting going on in this space.

For example, I don’t even know what to call this image. A chart? An infographic? You could call it a meme, but that’s not really what it is, that’s what it does. What is this thing and how does it work? Why is it so amenable to being shared and spread?

I read an interview a few weeks ago with Jim Messina about his long preparation for the reelection campaign, which entailed talking with many technologists about how best to shift their messaging. As I recall, Steve Jobs told him that he needed to rethink their social media campaign entirely, pointing out that the iPhone and Facebook were barely babies when Obama began running for President.

I wonder if this sort of “Truth Team” doublespeak + nameless image wonder isn’t part of the product of that rethinking. Just from looking at my own news feed (and the numbers attached to the image) it seems to be spreading fairly widely and wildly. There’s some combination of framing + presentation + timing that is working really well for the Obama campaign here and I’d love to get inside it.

Roberts’ Switch In Time

by chris on Jun.28, 2012, under general

Earlier today the PPACA – more commonly known as “Obamacare” – was upheld by the Roberts Court in a ruling which surprised many people (I was not surprised, but only because I had listened to some very smart people forecast what came to pass).

At the risk of speaking out of turn and depth, I would like to suggest that what we have witnessed today is “a switch in time that saved nine” for the 21st century.

President Obama has not (publicly) threatened any sort of court packing scheme as FDR did. But he has been running against the court ever since his 2010 State of the Union in the aftermath of Citizens United. As Adam Winkler at SCOTUSBlog noted, the Court now features a 44% approval rating after having been the most consistently highly regarded arm of the federal government in decades.

When you combine this context with:

- The weird and labyrinthine logic of the Court’s decision

- The widespread signals that Scalia was originally in the majority

- Roberts was red-eyed and downcast while reading the decision

I would like to propose the following analysis:

Roberts originally sided with Kennedy, Alito, Scalia, and Thomas in striking down at least part of the PPACA. However, at some point relatively recently he realized that if the PPACA was struck down it would mean that his Court could be cast as the most conservative and activist in history, allowing Obama to run strongly against it, and allowing his place (and Court) to be denigrated in history as the Lochner era now is.

So, as Adam Winkler has written, Roberts made a deal with the devil. He switched sides and supported the PPACA. But he did so in the most limited and bizarre way possible, using a rationale (mandate as tax) abandoned by the government early on, and one most easily framed as something no one likes (taxes). He slighted the Commerce clause, potentially weakening the foundation of all social legislation.

Most importantly: he gave himself credibility with a lay audience as a centrist, bipartisan, “balls and strikes” justice, one willing to go against the grain for what he thought the law to be.

Of course, Roberts is nothing of the sort (and you only need to read his past opinions to see that). He now, however, can be credibly seen to be that kind of Chief Justice. This decision will insulate him from charges of activism that Obama et al may wish to make – and even to run on – even while he prepares, this fall, to likely strike down affirmative action and a whole host of other causes.

The more I think about it the more I wonder if this outcome wasn’t one of the worst possible for progressives.

You get a flawed bill that you may or may not have liked anyway, weakened further by the Medicaid provisions (as I understand the Court to have ruled that the states need not expand Medicaid). In any case, you do not get to blow up PPACA and start over (I am not saying this is necessarily the right option, merely that it is now certainly a foreclosed option).

You do get Obamacare – moreover, Obamacare reframed as a tax – hung around Obama’s neck for the fall.

You do not get to run against a conservative activist court, potentially for a long time, as this case provides Roberts credibility to be the “balls and strikes” justice he most assuredly isn’t.

This is a “switch in time” that preserves the Roberts’ Court’s political legitimacy. And by executing it he’s revealed himself to not only be a committed conservative, but a wily one too, willing to play a much more influential long game. That is a terrifying specter for any progressive who cares about the Court to behold.

My Ignite Talk on User Generated Censorshop

by chris on Jun.27, 2012, under general

Last week I spoke at the 2012 MIT-Knight Civic Media Conference on user generated censorship.

You can watch it on MIT TechTV or embedded below: